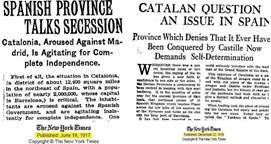

Catalonia is being accused of embarking in a feverish nationalist adventure to break up with Spain. Is this true? If so, who is the nationalist? And is it a temporal fever?

The history of Catalonia’s institutions dates back to the middle ages. The original set of Catalan institutions, however, was brought down after the War of Spanish Succession in 1714 and gave way to an occupation administration with an explicit goal of converting Catalonia into a mere province of the Kingdom of Spain.

The two attempts at decentralization in the last hundred years (1914 -1923 and 1931-1939) were crushed by military coups.

The two attempts at decentralization in the last hundred years (1914 -1923 and 1931-1939) were crushed by military coups.

Catalonia has never renounced its right to self-determination. On the contrary, the Parliament of Catalonia has passed a number of bills explicitly upholding it: Resolutions of the Parliament of Catalonia 98/III of 12 December 1989, 229/III in 1991, and Resolution adopted on 1 October 1998. The Catalan people have consistently delivered majorities in Parliament to parties in favour of more devolution or independence every time they’ve had the opportunity to participate in free elections.

Following this desire for greater autonomy, a draft of a new Catalan statute of Autonomy was approved in the Parliament of Catalonia by 120 out of 135 MPs. In 2006 the Statute of Autonomy was approved by the people of Catalonia in a binding referendum (73.9% voted Yes).

Following this desire for greater autonomy, a draft of a new Catalan statute of Autonomy was approved in the Parliament of Catalonia by 120 out of 135 MPs. In 2006 the Statute of Autonomy was approved by the people of Catalonia in a binding referendum (73.9% voted Yes).

The Spanish Constitutional Court considered in Judgment 31/2010 of 28 June, that a significant part of this Statute was incompatible with the 1978 Spanish Constitution. Yet only 10 out of 12 judges were able to sign the sentence and 4 members were executing the function of judge despite the expiration of their mandate. The Judgment violates Article 152.2[1] of the Spanish Constitution itself, because it modifies the will of the people expressed in Catalonia through a binding referendum.

As a result of the changes imposed by the Constitutional Court, the Statute currently in force devalued the definition of Catalonia as a nation and reaffirms the “indissoluble unity of Spain” several times. Many scholars have labelled the sentence as a unilateral breach of the Spanish constitutional pact between centre and regions.

After the sentence, Catalan society expressed its will in a series of massive demonstrations demanding the national recognition of Catalonia, and the power to decide its political future: among others, the million-strong demonstrations on 10 July 2010 and 11 September 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2016.

The Catalan authorities responded to these massive and repeated popular mobilizations. In 2012, after receiving an electoral and parliamentary mandate to hold a poll, president Artur Mas first tried to agree with the Spanish authorities and requested the transfer of the power to call the referendum.

Given the refusal of the Spanish authorities, the Catalan authorities passed through Parliament Act 10/2014, on popular polls other than referendums and other forms of citizen participation. This Act gave legal cover to the decree convening a non-binding popular poll on the political future of Catalonia. The bill was approved with 106 votes in favour and 28 against but was suspended three days later by the Constitutional Court.

In the conflict between the democratic will and legality, the Catalan Government chose to fulfil the mandate for which it had been elected. Mr. Mas decided on 14 October to replace this poll by a citizens’ participatory process. Yet the Catalan government’s involvement in the participatory process was halted on 4 November by a Constitutional Court injunction, at the request of the Spanish Government.

The poll eventually took place on November 9, 2014. It was carried out by 42,000 volunteers, and 2,344,828 people (about 40% of potential voters) took part, 81% of whose votes being in favour of independence. The poll had the support of the vast majority of local authorities, as 920 of 948 municipalities adopted motions in favour of convening the polls.

Twelve days after, the top prosecutor in Catalonia, by order of the Chief State Attorney, laid penal charges against four members of the Government for disobedience, corruption and embezzlement.

The trials of Artur Mas, Vice President Joana Ortega, Minister of the Presidency Francesc Homs and Minister of Education Irene Rigau took place in February 2017, and they were widely regarded as political. As the result of trials, all of the officials were banned from the public office at least for one year.

In 2015 pro-independence and pro-referendum coalitions secured 85 of 135 seats in the regional parliament. In order to fulfil their mandate the Speaker of the Parliament allowed a debate in the House on the conclusions of a parliamentary committee on the matters of a referendum and independence.

In 2015 pro-independence and pro-referendum coalitions secured 85 of 135 seats in the regional parliament. In order to fulfil their mandate the Speaker of the Parliament allowed a debate in the House on the conclusions of a parliamentary committee on the matters of a referendum and independence.

The debate was held in October 2016 and it resulted in a Resolution that gave a green light to the independence process. In January 2017 the TC urged prosecutors to lay further charges against the Speaker, along with four members of the Bureau. The prosecutors interpreted this request, laying charges against three of the four members identified by the TC. The omission of the fourth member is based on his political stance, in the prosecutors’ own words.

Over 400 pro-independence elected officials at municipal level have been charged by the Spanish authorities for their actions in support of the independence process over the last few years. These actions are going in range from using of symbols associated with setting up of the Catalan Republic to participating in political debates inside democratic institutions.

Over 400 pro-independence elected officials at municipal level have been charged by the Spanish authorities for their actions in support of the independence process over the last few years. These actions are going in range from using of symbols associated with setting up of the Catalan Republic to participating in political debates inside democratic institutions.

Spanish authorities offer no possibility of an agreed settlement of the Catalan question. The Spanish Government, without having challenged the legitimacy of the party manifestos presented at these elections or the outcome, is preventing the implementation of the electoral mandate expressed by the majority of the people of Catalonia.

Spanish authorities offer no possibility of an agreed settlement of the Catalan question. The Spanish Government, without having challenged the legitimacy of the party manifestos presented at these elections or the outcome, is preventing the implementation of the electoral mandate expressed by the majority of the people of Catalonia.

The Spanish institutions have repeatedly prevented the expression of the democratic will of the Catalans, and the Spanish Government has failed to comply with as many as 34 rulings of the Spanish Constitutional Court in favour of Catalonia. In all, thirty-four sentences: three refer to university student grants, three to the environment, four to culture and twenty-four to social services.

The Spanish government and courts are caught in a nationalistic fever and are irresponsibly cornering Catalan institutions and its citizens. How?

(a) Freedom of expression and opinion are not fully granted in Spain

Article 20 of the 1978 Spanish Constitution recognizes the right to freedom of opinion and expression. Nevertheless, the Spanish authorities have laid criminal charges in connection with various expressions favourable to the creation of a Catalan Republic.

- Xavier Casanovas, a teacher at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, was fined 601 euros for speaking in Catalan with the Spanish police.

- French citizen Claude Lefèvre was searched and insulted because of wearing a sticker with the Catalan flag.

(b) Free exercise of political representation is not fully granted in Spain

Article 23.1 of the Spanish Constitution also recognizes the right of political participation through freely chosen representatives, which is reflected in the guarantee of the inviolability of the members of the Parliament of Catalonia in Article 57.1 of the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia. However, Spanish authorities have laid several criminal charges in respect of opinions expressed in the Parliament of Catalonia and other local parliaments.

- Joan Coma, a Vic local councillor was judged for inciting sedition for saying “To make an omelette you must break some eggs”.

- The Spanish Constitutional Court urged state prosecutors to lay charges against the Speaker of the Parliament of Catalonia, Mrs. Carme Forcadell and three out of four members of the Bureau, for allowing a debate in the House.

(c) The impartiality of justice is not guaranteed in Spain

Article 159 of the Spanish Constitution and a Law 2/1979 that regulates the composition of the Constitutional Court recognize the necessity of the impartiality of members.

- The current president of the Spanish Constitutional Court is proven to be a sympathizer of the ruling party Partido Popular.

- When the Constitutional Court urged prosecutors to lay charges against the Speaker of the Parliament, along with four members of the Bureau, the prosecutors interpreted this request, laying charges against three of the four members identified by the TC. The omission of the fourth member is based on his political stance, in the prosecutors’ own words.

[1] https://www.boe.es/legislacion/documentos/ConstitucionINGLES.pdf – Pg. 45